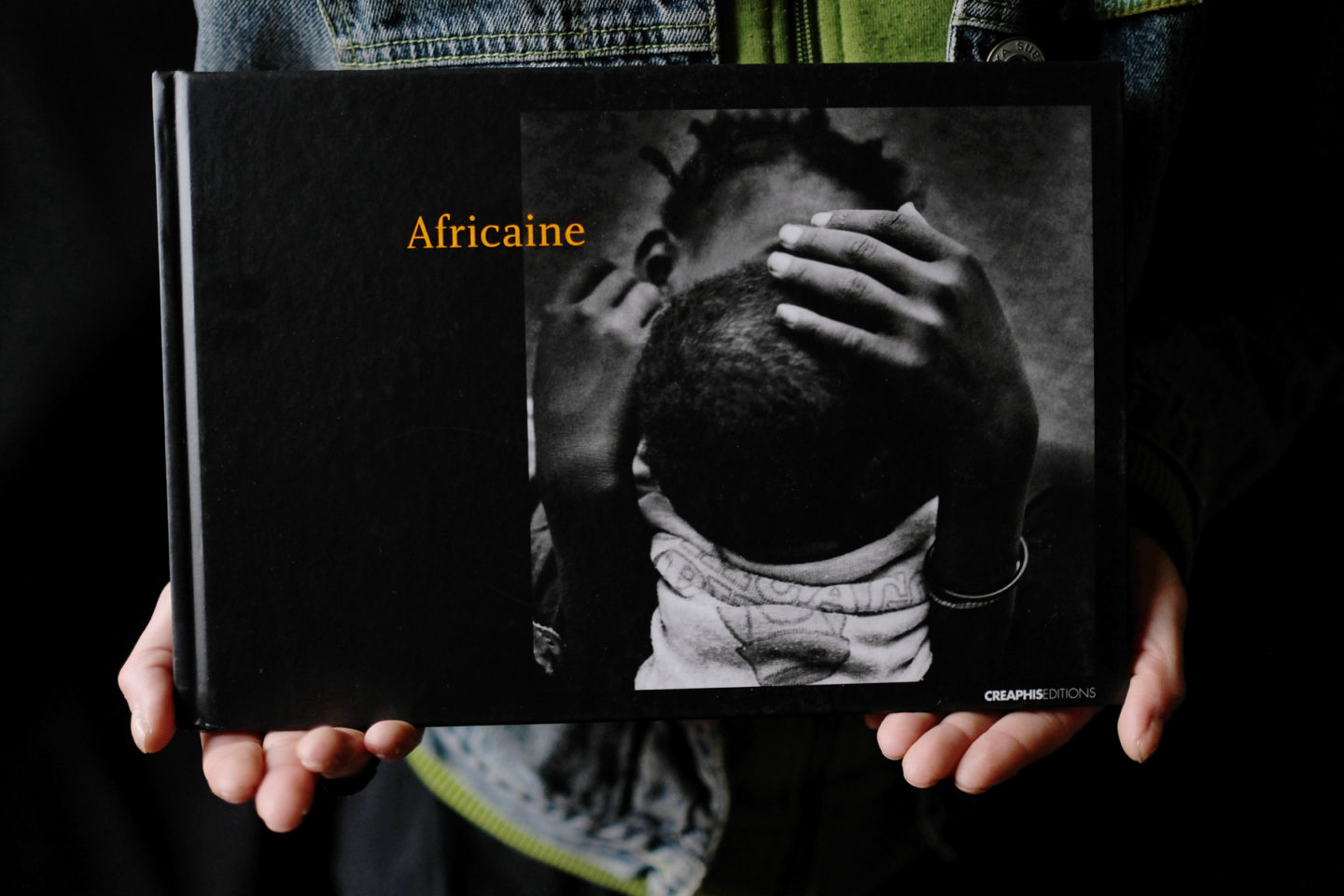

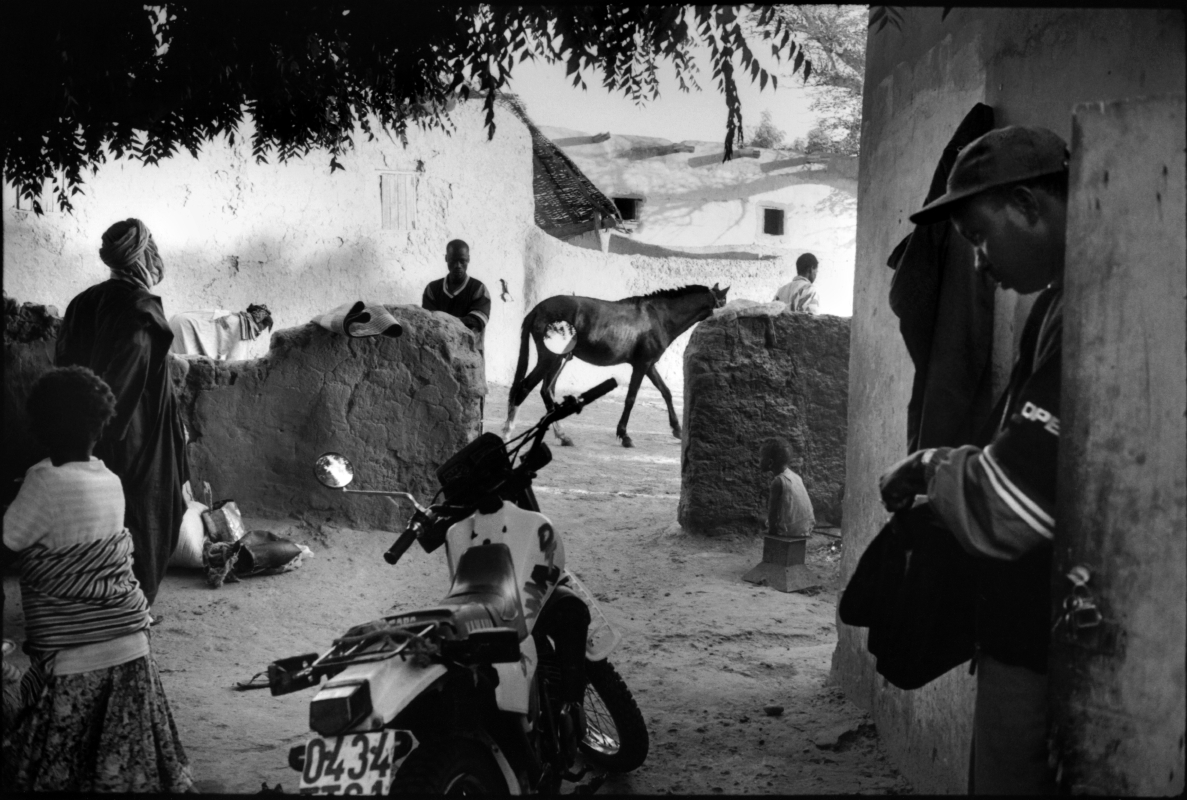

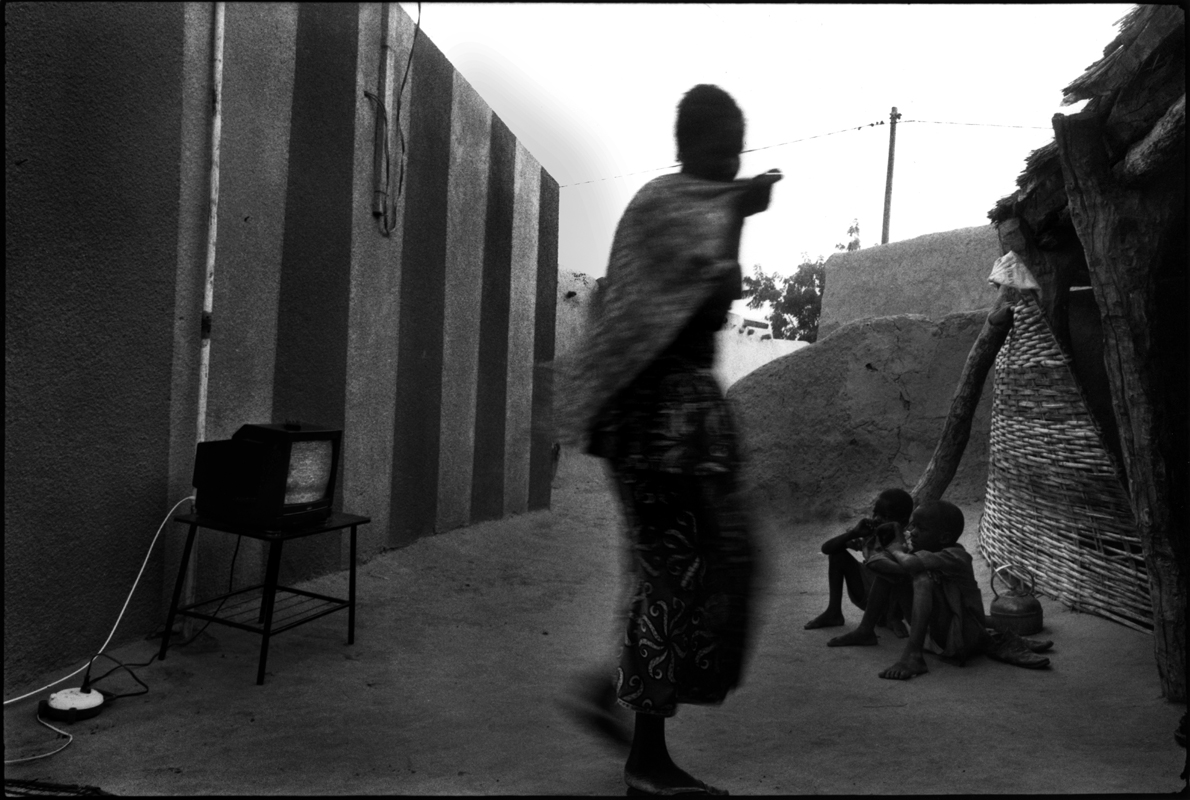

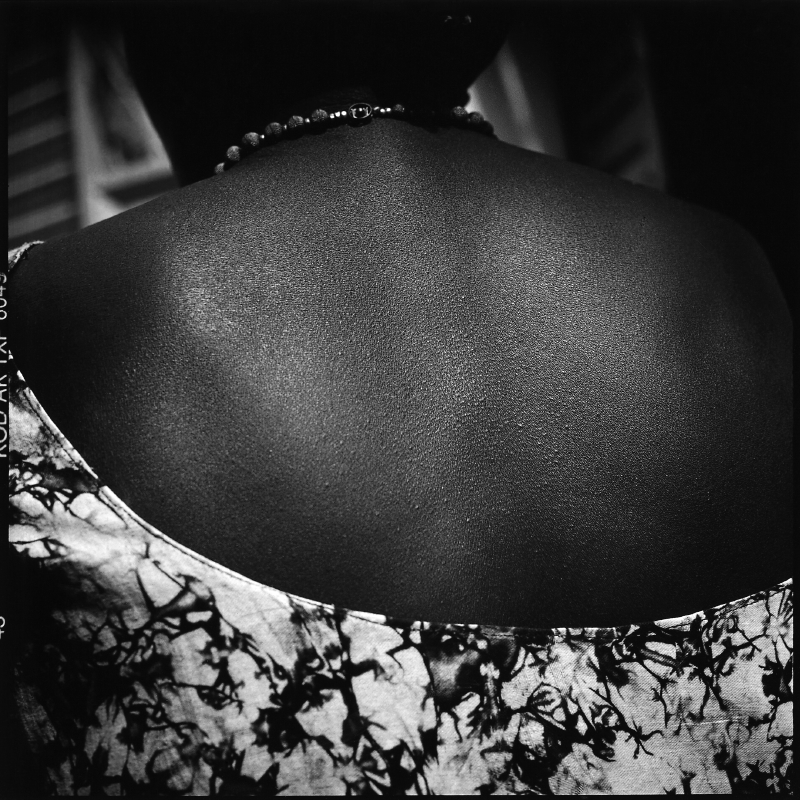

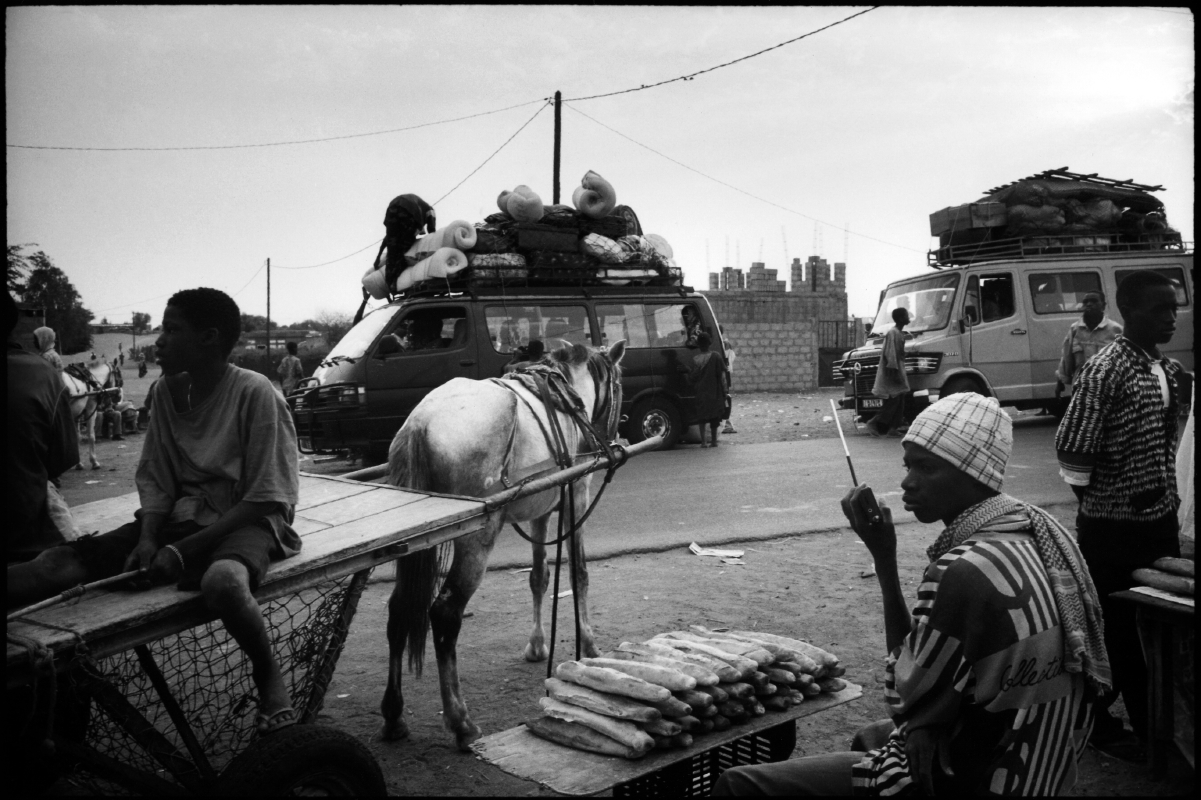

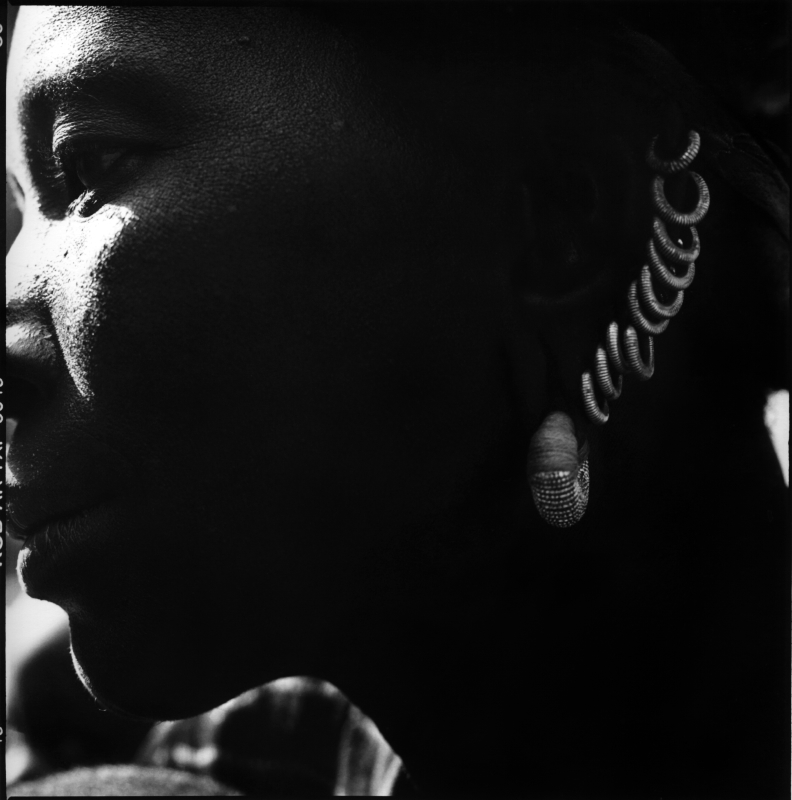

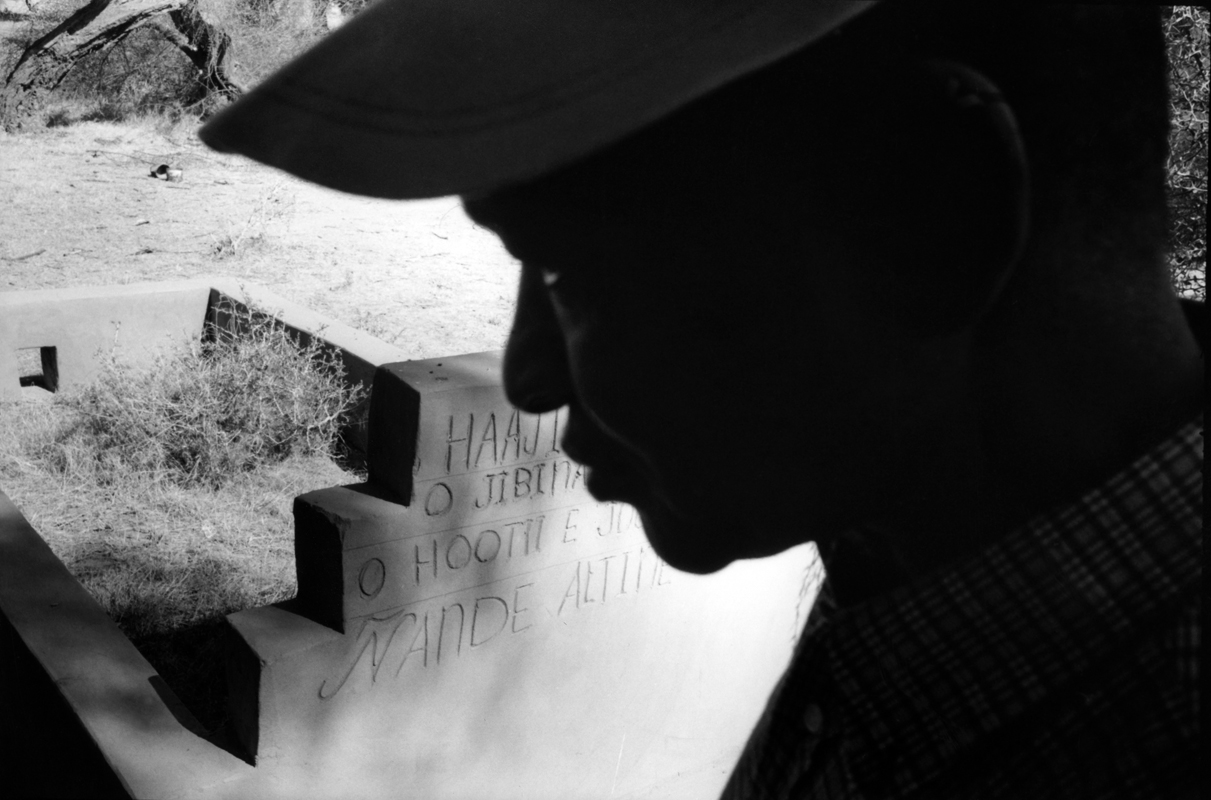

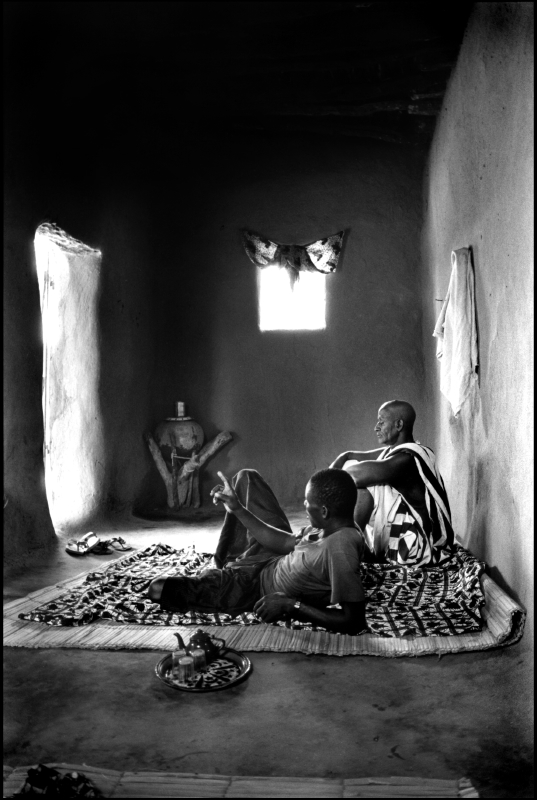

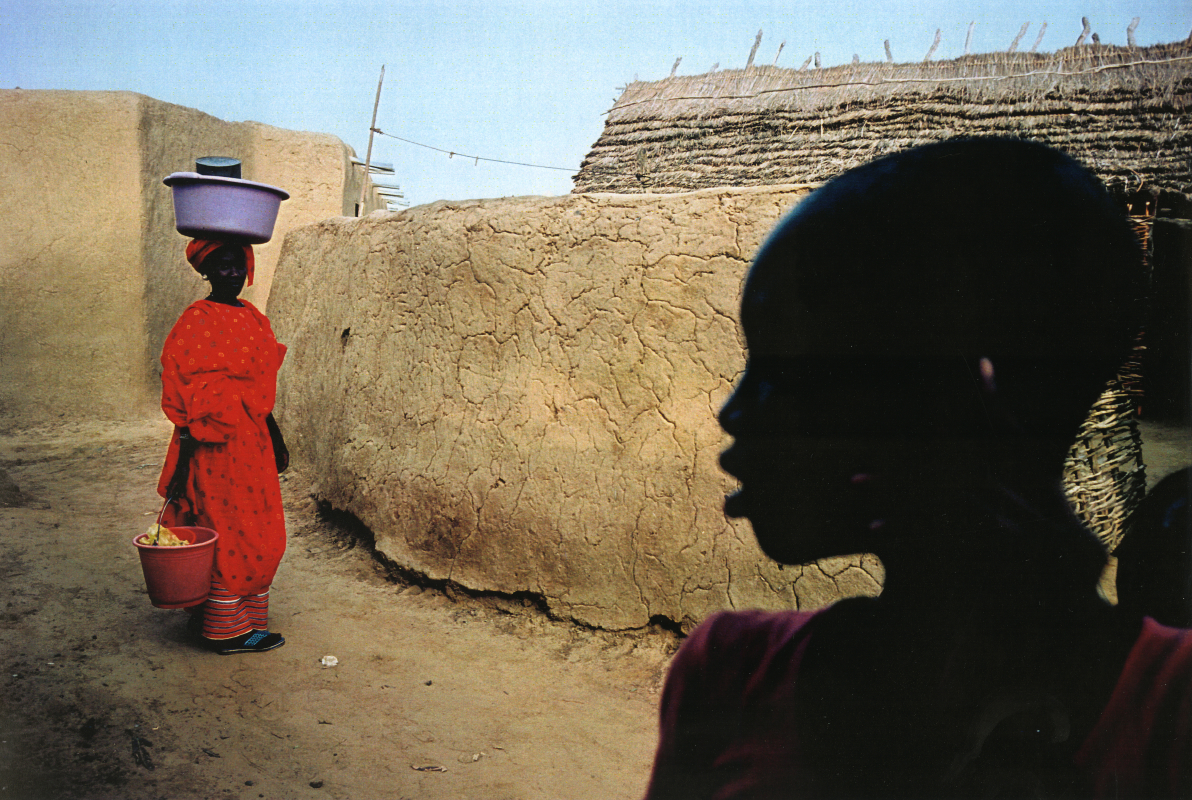

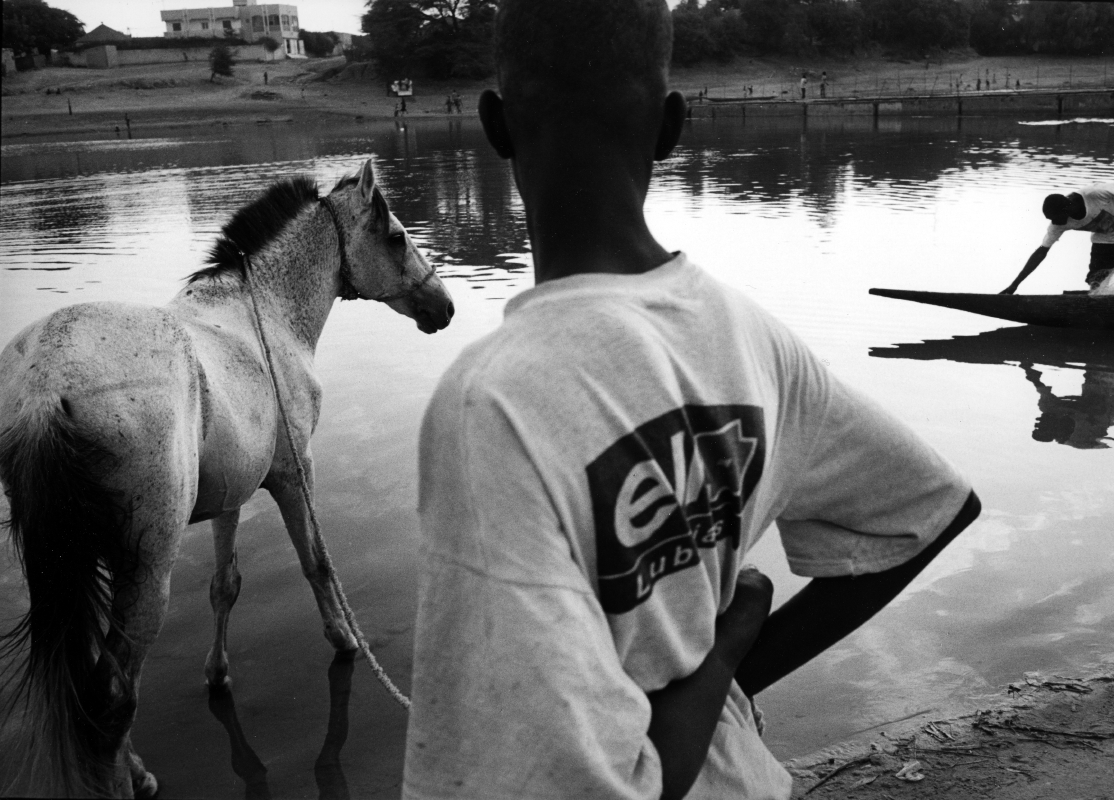

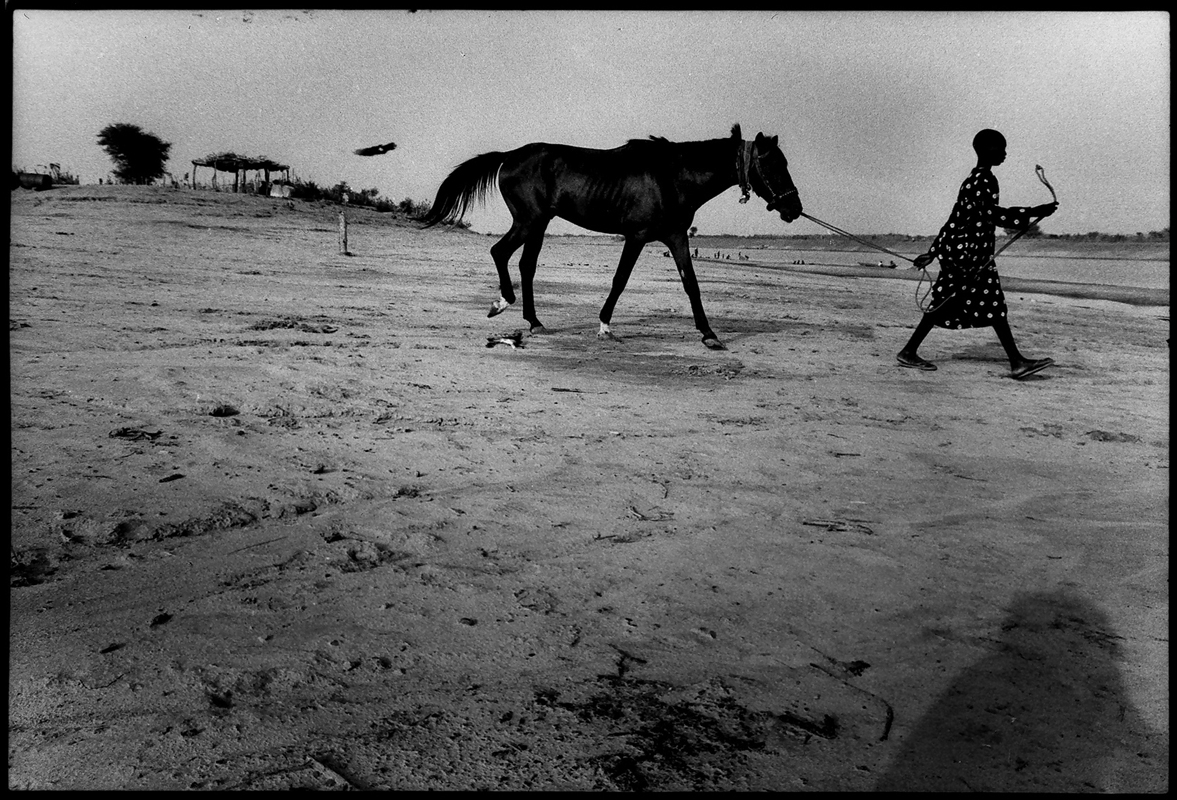

Pendant 25 ans, la vie du village de Ndioum, au bord du fleuve Sénégal.

Un livre aux éditions Créaphis

avec une nouvelle de l’écrivain sénégalais Boris Boubacar Diop.

For 25 years, I took photos of life in the village of Ndioum, on the banks of the river Sénégal. A book retracing these photos was published by Créaphis with a short story by the Senegalese writer Boris Boubacar Diop.

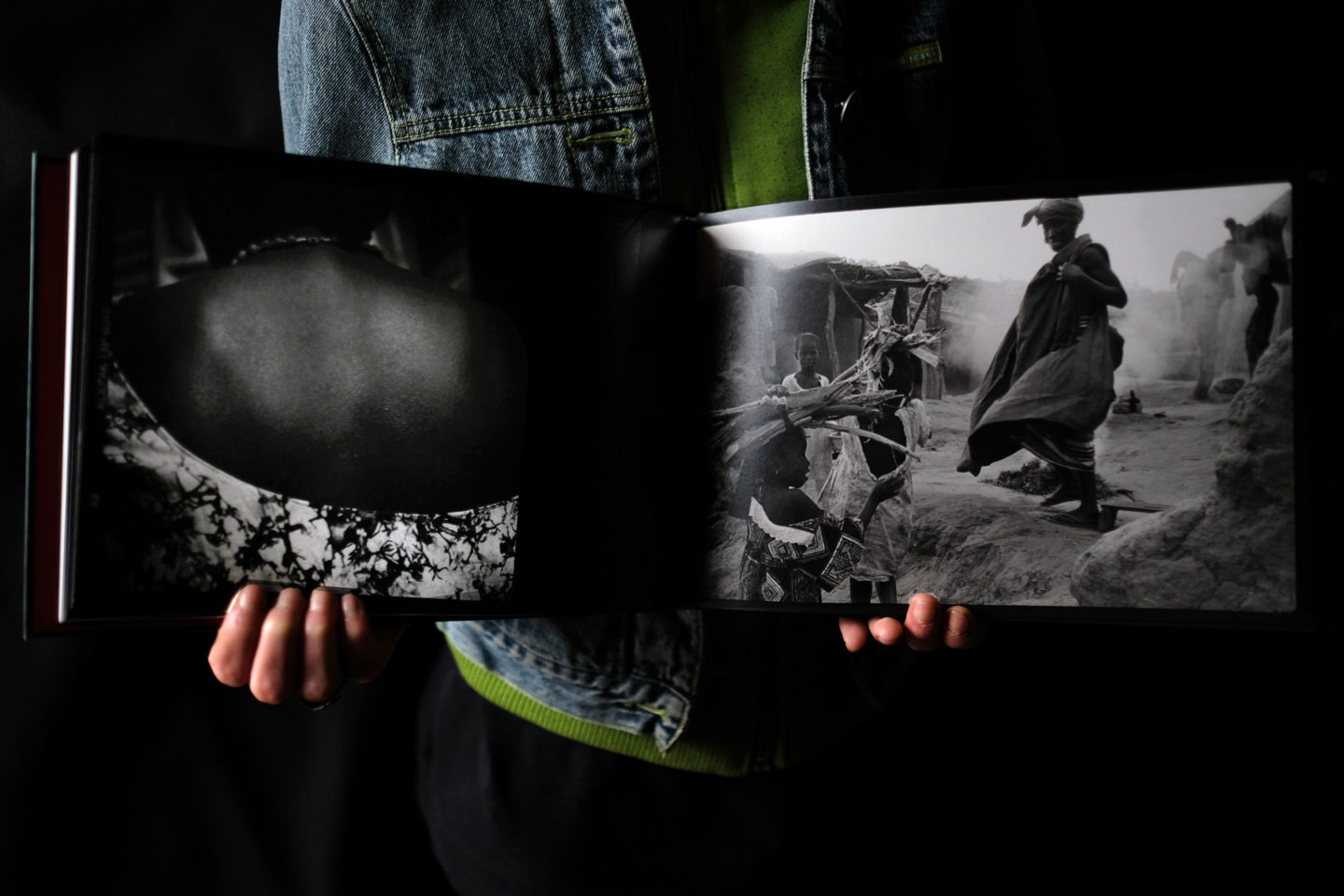

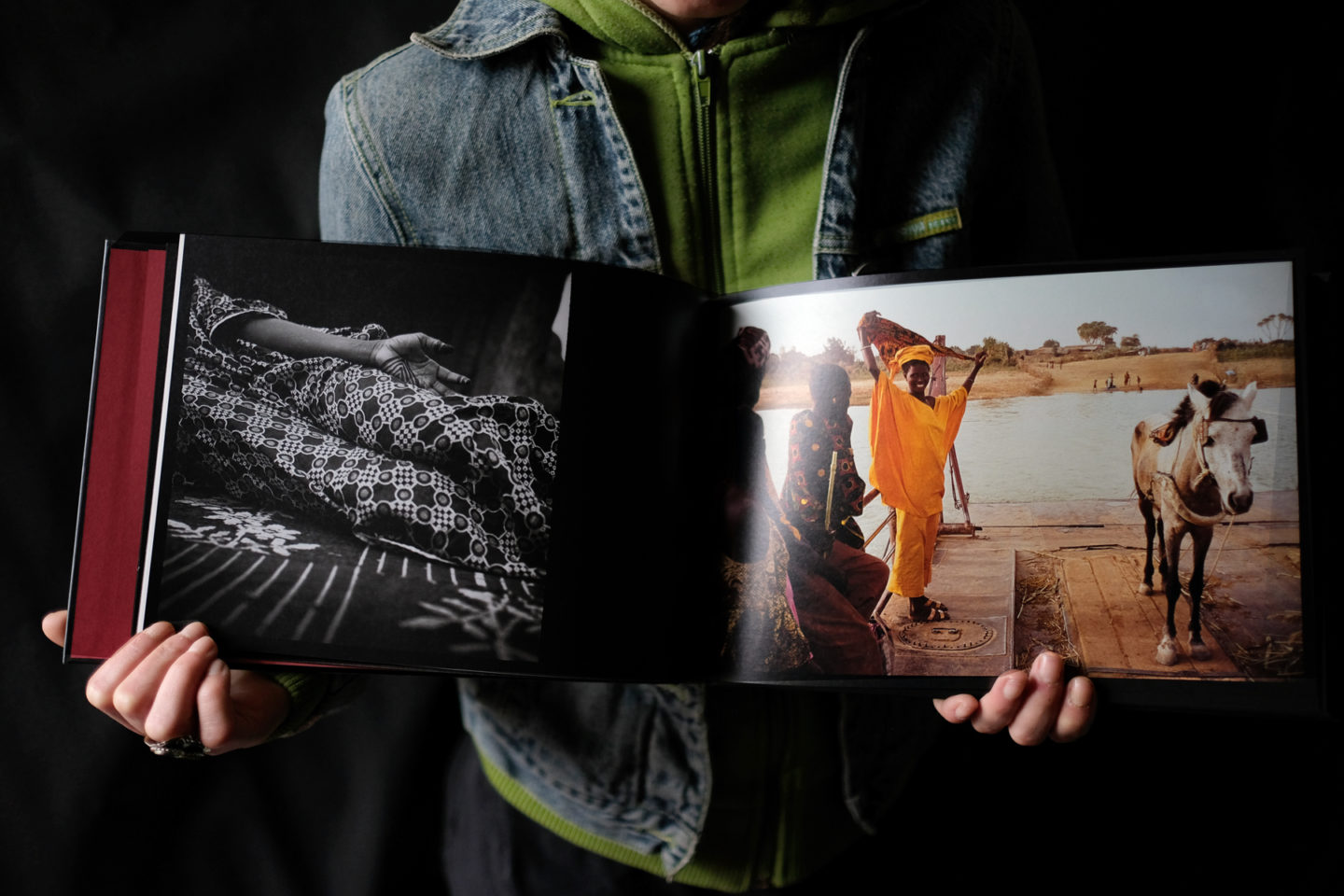

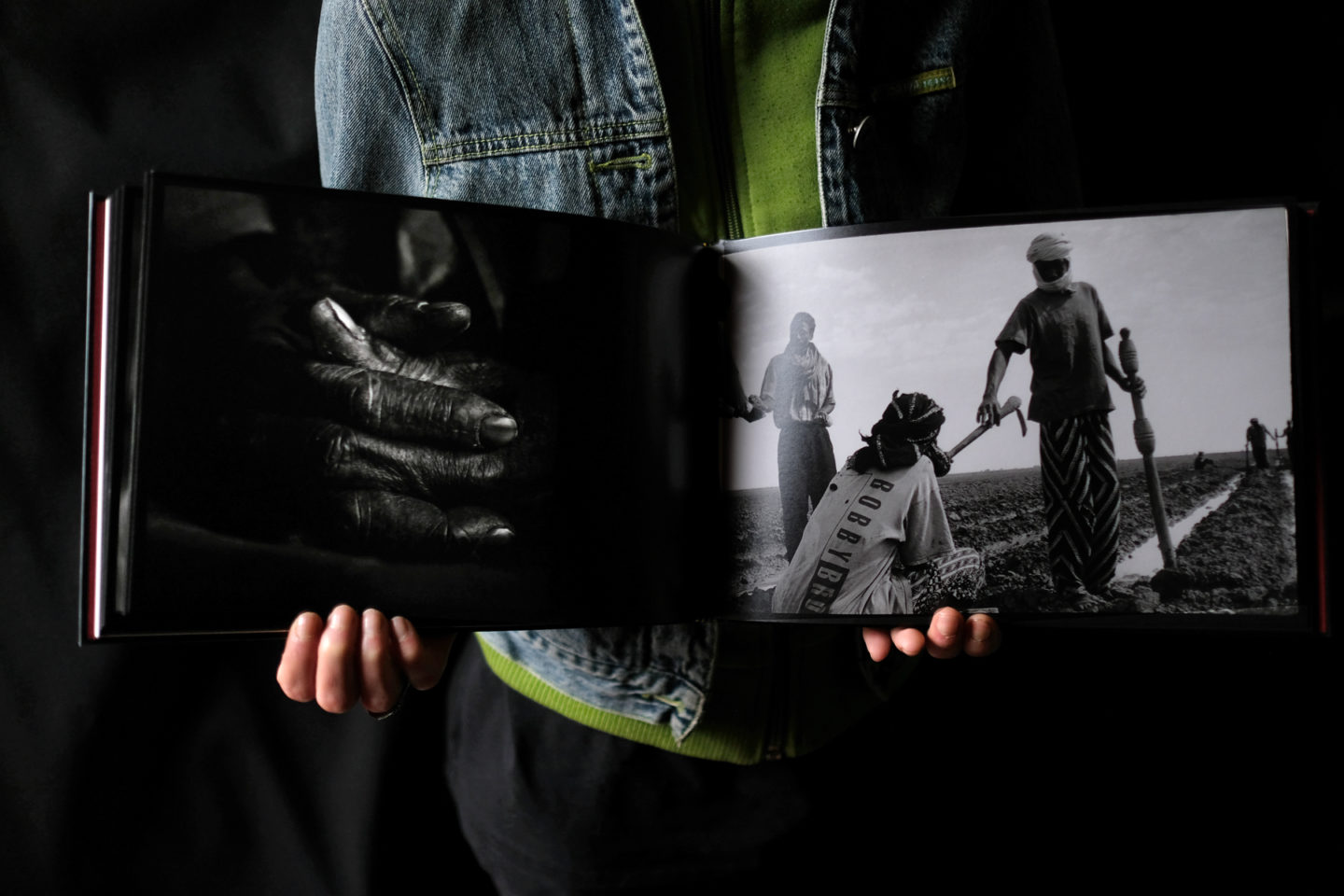

Ndioum est un village du Sénégal situé sur le Mayo Worgo, (le Doué), le bras le plus au sud du fleuve Sénégal. Au nord, le Mayo Rewo fait la frontière avec la Mauritanie. Cette partie de la région administrative de Saint Louis est appelée le Fouta Toro. La population y est en majorité Haal pulaar, nom qu’elle se donne elle même qui signifie « Ceux qui parlent le pulaar », la langue peul.

Les peuls font partie de cette communauté comme sous groupe. Les colonisateurs français appelèrent ses habitants « Toucouleurs », terme controversé, (voir les travaux du professeur Aboubacry Moussa Lam), ce nom venant de la francisation du mot « Tekrour », nom du royaume situé dans cette vallée du Sénégal dès le 4 ème siècle, vassal de l’empire du Ghana. Ils viendraient du Haut-Nil, aujourd’hui le Soudan, comme la plupart des autres peuples d’Afrique de l’Ouest. Ndioum compte environ 12 000 habitants.

Ndioum est la déformation de ndioumtane qui signifie cigogne.

Ndioum is a village in Senegal located on the Mayo Worgo, (Doué), the southernmost branch of the Senegal River. To the north, the Mayo Rewo forms the border with Mauritania. This part of the administrative region of Saint Louis is called the Fouta Toro. The majority of the population is Haal Pulaar, a name it gives itself which means « Those who speak Pulaar », the Fulani language. The French colonizers called its inhabitants « Toucouleurs », a controversial term, (see the work of Professor Aboubacry Moussa Lam), this name coming from the Frenchization of the word « Tekrour », name of the kingdom located in this valley of Senegal since the 4th century, vassal of the empire of Ghana. They would come from the Upper Nile, now Sudan, like most other West African peoples. Ndioum has about 12,000 inhabitants.

Ndioum is a deformation of ndioumtane which means stork.

Vous quittez Ndioum et descendez le fleuve Sénégal, vous vous laissez glisser jusqu’à la mer, à Saint-louis.

D’une de ses plages, au début du XIV ème siècle, sont parties deux cents pirogues pour traverser l’océan Atlantique, affrétées par le roi Aboubacar II , neveu de Soundiata, le fondateur de l’empire du Mali .

Aboubacar II était persuadé qu’il y avait une autre terre de l’autre côté de l’océan, en suivant le cours du « fleuve qui coule dans la mer ».

Une seule pirogue revint. Son commandant raconta qu’un très fort courant avait enseveli le gros de la flotte, mais que quelques navires avaient atteint une autre terre, un autre continent.

Le roi décida de tenter lui-même l’aventure et, à la tête de deux mille pirogues, pris la route de l’Ouest. Aucune ne revint jamais.

C ‘était en 1312, cent quatre-vingts ans avant Christophe Colomb.

(d’après l’historien arabe Shihab al-Din al-Umari (1300-1349)

You leave Ndioum and go down the Senegal River, you let yourself slide down to the sea, to Saint Louis.from one of its beaches, at the beginning of the 14th century, two hundred pirogues left to cross the Atlantic Ocean, chartered by King Aboubacar II, nephew of Soundiata, the founder of the Mali Empire. Aboubacar II was convinced that there was another land on the other side of the ocean, following the course of the « river that flows into the sea ». Its commander told that a very strong current had buried the bulk of the fleet, but that some ships had reached another land, another continent.The king decided to try the adventure himself and, at the head of two thousand dugouts, took the road to the West. This was in 1312, one hundred and eighty years before Columbus.

(according to the Arab historian Shihab al-Din al-Umari (1300-1349)